What a Long Strange Trip It's Been

GALAGA & GIRLS IN GLASSES: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 1

I got started on my writing career at the tender age of 19, thanks in no small part to the two great loves of my teenage life: girls and video games. I had zero clue at the time how much each of those passions would influence my career.

Technically, I had been writing for quite a while at that point. I wrote my first story probably six or seven minutes after I first felt comfortable with the whole “reading” thing. By my late teens I had produced fifteen or twenty short stories that I liked, a slew of poetry that’s not even worth acknowledging, and one fantasy novel that I completed at age fourteen, revised at age sixteen, and recognized for unreadable garbage around my seventeenth birthday.

But, aside from getting me admitted to the Georgia Governor’s Honors Program (or “GHP,” as it’s fondly remembered by hundreds of nerds state-wide) in my junior year of high school, I had never profited from anything I had put down on the page. (And yeah, that was back when people still wrote things on paper. I typed out every horrible word of that fantasy novel on a manual typewriter. When Dad eventually brought home an electric model—complete with an “erase” button that would lift the ink of your typo right off the page—I thought I’d died and gone to literary nerd heaven.)

But I digress. The point is, by age 18, I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I had started college in pursuit of an English degree, but I was still pretty hazy on the whole “accomplishing actual goals” thing.

My older sister, on the other hand, had decided to go to college at Mercer University in Macon, Georgia. After dabbling with drama for a while, she settled in to become a teacher, got her degree, and eventually landed a position at a small private school not far from Macon. And so it was that, a couple of months before my 19th birthday, I drove down to Macon to hang out with her for a week.

During that week—I think it was on a Wednesday—I decided to go out to the Macon Mall, hunt down the arcade, and spend what little money I had on video games, because I apparently hated money and wanted to get rid of it as soon as possible.

After a few stimulating rounds of Dig Dug, I had depleted my stockpile of quarters and was about to walk out, when the arcade attendant caught my eye. She was a petite, dark-haired beauty with little wire-rimmed glasses and a smile that made me dumber than I was already, but for some reason she seemed to think I looked all right too, and we started talking.

The talking led to a date, during the course of which I babbled at some length about my writing ambitions, and when I finally paused to take a breath, she said the words that would, at the risk of sounding over-dramatic, alter the course of my life forever: “Hey, I know some comic book artists. Would you like me to introduce you?”

COMIC ARTISTS & OTHER GREAT OLD ONES: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 2

Regarding comic books: I grew up reading them. I sort of grew up steeped in them. I got started at age seven, when my eleven-years-older brother, Clint, came home from college with a big Xerox paper box full of wrinkled-up, abused Marvel comics and said, “Here, you can have these.” So by age 18, I had a pretty solid working knowledge of both the DC and the Marvel universes, and dearly loved The X-Men, Iron Man, and Batman.

Had I ever considered writing comic books? Nope. Not once.

But the arcade attendant—with whom, sadly, things did not work out after about three dates—took me and introduced me to a couple of comic book artists she knew from Macon: Tony Harris and Craig Hamilton.

Craig had already gotten fairly well established at that point, and was working on a jaw-droppingly gorgeous Peter Pan project. Tony was in the very beginning stages of his career, working on an independent comic called “B.L.A.D.E.” and, not long after that, some fully-painted issues of the “Nightmare on Elm Street” comic. I showed them some of my short stories, and Tony really sparked to one called “Nightrunner,” which I did not realize at the time was the name of Cutter’s wolf in “ElfQuest.”

Unintentional Elf references aside, Tony told me he’d like to see what he could do about getting “Nightrunner” published, and not long after that he called me up and said he had things set to get the story printed, complete with his accompanying illustrations, in an anthology publication called “Beautiful Stories for Ugly Children.”

That deal ended up not going through. I don’t remember why not. But what had gotten started was my working relationship with Tony, which would go on for many years. Tony introduced me to Meloney Crawford Chadwick at Harris Comics, which led to my first sale: an issue of “Vampirella,” on which everything that could possibly go wrong did go wrong, starting with my really really awful script. Awful script or not, I got paid the princely sum of four hundred dollars for that issue, which I promptly spent on my first-ever word processor, a clunky little machine with a tiny screen that displayed amber words on a black background. (It would be a couple more years before I got my hands on an actual home computer.)

Tony also introduced me to Joe Phillips, with whom I put together a pitch for Innovation Comics to adapt an H.P. Lovecraft story. The pitch got approved, and I was on the proverbial Cloud 9. The story was “The Dreams in the Witch House,” which I absorbed and just adapted the hell out of, turning out a 48-page script in two or three weeks. I was anxious to get Joe’s feedback on it, and faxed it over to him (yes, faxed, because e-mail was not a thing yet) — only to have him call back and tell me that Innovation had gone out of business. That was the first Great Big Huge Heartbreaking Letdown of my career. It’s the kind of thing that freelance writers have to get used to.

Joe went on, however, to introduce me to an editor at Dark Horse Comics who would prove to be enormously influential for me…

…but first I want to address the serendipitous way I got into comics. Around 2003 or 2004 I was at a convention and ended up on a panel discussion next to Peter David. (For those not familiar with the name, Peter David is a well-known, very successful comic book writer and novelist.) One of the audience members posed the question for each of us to answer: “Breaking in seems to be somewhere between hard and impossible. How did you get into comics?”

So I said, “Well, I might be able to give you a little hope,” and I told the story about meeting the girl in the arcade and being introduced to her comic book artist friends. And Peter David interrupted me and just totally started making fun of me for it. He put on a Scottish accent and said, “The situation has not improved!” and just made joke after joke at my expense. (To be fair, given my generally clumsy delivery and the looks on some of the audience’s faces, I probably deserved it. There’s a reason I’m a professional writer instead of a professional speaker.)

The thing is, I had a point to follow up with, but I tend to get flustered when I’m surprised, and I was quite surprised that this industry vet was just laying into me, in public, ridiculing me for implying that anyone could fall into the same circumstances that I had. So I forgot the point I was going to make and just mumbled something and turned red from embarrassment.

But THIS is the point I was going to make: I got into the industry because I got some face-time with people already working in it. I established a connection, and got them to look at my material, and that got my foot in the door. Are YOU going to have the exact same thing happen to you? No, probably not. But you can get face-time with working professionals just about any weekend of the year, by going to comics conventions. There are artists and writers there, sitting at their tables all day long, making themselves available for you to just walk up and talk to them. If I had known about that before I met Tony and Craig, I would have been going to conventions already.

ONE FOOT IN THE SARCHOPHAGUS: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 3

It’s hard to describe how important having a good editor is.

One universal truth is that every writer needs an editor. It doesn’t matter who you are, or how skillful or talented you are, or how many millions or billions of dollars you’ve made, if you don’t have an editor your work won’t be as good as it can be. Sometimes that’s because a good editor can be a sounding board for new ideas, or help you make good ideas into great ones. But most of the time it’s because a good editor will tell you “no.” As in, “No, you shouldn’t include this sub-plot, because it undermines what the whole story is about,” or “No, you shouldn’t use this bit of description, because it breaks the tone and ruins the immersion,” or “No, Jar Jar Binks doesn’t really work as a character.”

I was incredibly fortunate that the first editor I worked with at some length was very, very good. His name was Dan Thorsland, and he was the editor at Dark Horse Comics to whom Joe Phillips introduced me.

Dan didn’t have to give me the time of day but, for whatever reason, he chose to do so (maybe Joe was very persuasive), and we ended up on the phone one weekday afternoon. I told him I was just starting out, and that nothing I’d written had been published yet, because my issue of Vampirella was in something like its sixth month of delays. (It eventually came out a full nine months past its deadline.)

So Dan started describing a page of a comic book he happened to be looking at just then. “There’s a guy getting off a bus,” he told me, “and he’s carrying an oblong box under one arm. And the caption reads, ‘The stranger carries an oblong box under one arm.’”

I burst out laughing.

Apparently that pleased Dan, because he said, “Now that’s the proper reaction,” and he really started talking to me in earnest - in fact, that conversation became my first lesson in Comic Book Scriptwriting 101. “If the art shows you something, really clearly shows it, then you DO NOT describe it in a caption,” Dan said. “That’s what you call ‘explainy,’ and it’s bad writing.”

He and I went on to have about an hour-long conversation, just sort of feeling each other out, figuring out if the creative chemistry was really there or not; we talked about favorite comics and novels and movies, and our individual senses of what made a good story, and at the end of it he decided to give me a shot.

That shot became a 16-page, two-part story in the anthology title “Dark Horse Comics.” (Yes, the series had the same name as the company.) It was a story called “Cargo,” set in the “Aliens” universe, and when all was said and done, and I held my free copies of the actual comic book in my hands…

…it wasn’t very good. I was still on the vertical side of the learning curve, and there were just a lot of things I could’ve done better. But thanks to Dan Thorsland, it wasn’t awful, and also thanks to him I got introduced to an artist I’d go on to work with on quite a few other projects: John Nadeau.

An aside on John Nadeau: I don’t think I’ve ever met a comic book artist who’s more stable, more reliable, and more grounded than John. He started out as an engineering student, and it’s given him an amazing connection to what’s real and physical. Not to mention that he’s insanely talented.

So. “Cargo” might not have been brilliant, but it did serve one incredibly important purpose, which was that it proved to Dan Thorsland that I was a writer who could be given a task that would actually get done, and done on time. You wouldn’t believe how rare that is, apparently, among creative people. I got the work done on time, the work was not horrible, and I was friendly and relatively easy-going.

(I say “relatively” because, especially early on, I’d occasionally flip out and lose my $#!+ over some minor detail that didn’t exactly fit my vision. Sometimes I still flip out - if the issue is big enough - but I try to keep it under control as much as possible. Here’s Rule #1: don’t flip out and lose your $#!+. It makes you look unprofessional and can cost you jobs. Depending on the circumstance, it can also be a lot easier said than done.)

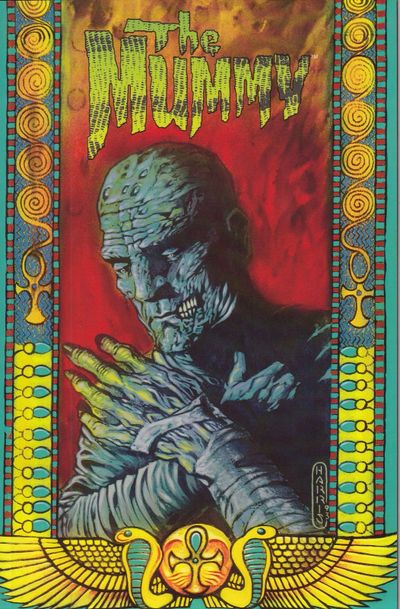

So after “Cargo,” the next firm project I got brought me back to working with Tony Harris, this time under Dan Thorsland’s watchful eye. It was an adaptation of the 1932 Boris Karloff film, “The Mummy,” and it gave me a new appreciation for the whole concept of “on-the-job training.”

ON-THE-SCRIPT TRAINING: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 4

I wound up in a movie theatre tonight, seeing “The Avengers” for the fourth time, and I think I’ve now decided that I really, truly like that film. It’s not perfect by any means, and I found myself wondering why they didn’t just knock Stark Tower out from under the tesseract (it would have been at least worth a shot), but I enjoyed it. Mark Ruffalo and the Hulk totally steal the whole picture.

I don’t remember the exact conversation I had with Dan Thorsland at Dark Horse that resulted in me writing an adaptation of “The Mummy.” Tony Harris may have told Dan that he wanted to work on it with me, or Dan may have brought it up independently of Tony. (It was a really long time ago, and I never bothered keeping a journal.) But however it happened, in either late 1990 or early 1991, I landed this job, and I do know that one of my first questions to Dan T. was, “Is there any particular way you want me to approach this?” And that his answer was, “Yeah - watch the movie a bunch of times and then write the script.”

I didn’t find that directive overly helpful.

What became clear was that Dan Thorsland did not consider it his job to teach me how to write an adaptation. He wanted me either to figure it out for myself, or get educated somewhere else. Well, at that point, everyone I knew in comics was either a) an artist, or b) Dan Thorsland, so I settled on figuring it out for myself.

Welcome to On-The-Job Training!

Now, please understand, I bore Dan no ill will for this approach. It actually pleased me - I felt as though HE felt that I was perfectly capable of doing this, so I took it as a sign of respect. It reminded me strongly of my first term in college, when one of my classmates asked our Sociology professor if he was going to tell us which topics would be covered on the first exam. The professor’s response was, “Of course not! That’s your job!” And I thought, Wow, I’m in college! Cool!

Anyway. Dan did send me a copy of the movie (on pristine VHS, still in the plastic). So I spent a couple of days staring at the box, trying to decide how to go about writing the actual script.

Comic book scripts are their own creatures. There are fundamental differences between scripts for comics and scripts for TV, movies, stage plays, and video games. First and foremost, the images are static. There can be no, “John takes the gun out of the drawer, spins the cylinder, and slips it into his pocket.” If you want to convey that information, you need three images:

- John stands in front of the drawer, which he’s pulled open. He’s holding the gun in his right hand, eyeballing it critically.

- New angle on John, closer in on the gun, as he spins the cylinder with his left hand.

- Turning away from the drawer, John drops the gun into his pocket.

There are quite a few great big awesome books on the subject of creating comics, and I’m not going to try to explain everything about how comics work here, because those books do it better.

(Seriously, pick up “Understanding Comics” by Scott McCloud. It’ll blow your mind.) But I’ll touch on a few essentials, and the static nature of the images is one of them. For “The Mummy,” I knew I had to isolate the most important images, the crucial visual bits that advanced the story and established the characters.

And eventually I settled on probably the most obvious method possible: I put the tape in the VCR, hit PLAY, and every time the movie cut to a new significant image, I hit PAUSE and scribbled down a description of that image in my notebook. It looked sort of like this:

- Long shot of Ardeth Bey in silhouette, riding a horse that’s being led by a servant, approaching the house

- Girl in the house hears a knock at the door

- Ardeth Bey at the door as the girl opens it

- Zoom in on Ardeth Bey’s eyes as he starts to hypnotize her

Each of those images became one panel in the script. (I would go back later and copy down all the dialogue. I had no Internet to look up the screenplay, and none of my local libraries carried it.)

Then it actually became something of a math problem - a formula that, with slight modifications, I would end up using on every single comic book project I ever worked on after that. Basically I took the number of panels I had jotted down (around 170) and divided it by the number of pages the project was allotted (48). That gave me 3.5, which was the average number of panels I could have on a page and still tell the story in a coherent way.

Of course you can’t have half a panel on a page, but all that meant was that some pages could have four panels and others might only have one or two. Mix and match.

So I mapped out how the panels would fall on the pages, and kept as much of the movie’s dialogue intact as I could, and eventually turned in my script. To my recollection, Dan Thorsland didn’t change a single word of it.

HUNGER & OTHER MOTIVATING FACTORS: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 5

I never had any money growing up.

Both my parents worked, but not at jobs that paid very well, and especially when I was small (before Mom re-entered the work force, and was spending her days taking care of my scrawny, screaming little ass) there were quite a few months when the bank account showed a nice, round $.05 after all the bills were paid.

This kind of poverty (and we were definitely below the poverty line) was not uncommon in the tiny little town in Georgia where we lived. What was uncommon was that my parents, each a product of small-town, rural life in the 1930’s, had found each other. Neither of them went to college, and yet they were both sort of scary-smart, and STICKLERS LIKE YOU WOULD NOT BELIEVE for correct grammar. To this day my grammar remains very close to flawless, and I’ll actually stop and correct myself when I’m talking if I flub up. I can’t help it.

I’ve often thought that my parents were, essentially, a couple of very high IQ’s and a heaping helping of pride away from being what Southerners call “poor white trash.” But those IQ’s and that pride were like a high steel wall, and things like wifebeater tank tops, food stamps, and cars on blocks in the front yard remained on the other side of that wall. Permanently.

But I digress. The point is: I never had any money.

This lack of funds carried over solidly into my college years. And I know, college students are always broke. I suspect I was probably more broke than most. I attended the University of Georgia, and worked part time at Spencer Gifts in the Athens mall, selling raunchy greeting cards and raunchy T-shirts and the occasional “personal massager” (also raunchy).

Just down the way from Spencer Gifts was a little Chinese restaurant (operated entirely by Mexicans), and for the grand total of one dollar I could get an egg roll and a little cup of sweet-and-sour sauce to dip it in. That cup of sweet-and-sour was very important, and I always asked for a spoon when I got the egg roll, because as I dipped the egg roll in the sauce, little bits of it would fall out and accumulate in the cup. Then, when the egg roll itself was gone, I had a whole other part of the meal: sweet-and-sour sauce soup!

Having an entire dollar was important, because it meant I could eat that night, but there were plenty of nights when I didn’t have that dollar and went hungry. (I know, I know, I could have bought groceries for cheaper than eating out and brought a sandwich to work with me, but you have to remember that I was twenty years old and a complete dumbass.)

Anyway, I scraped by on what little funds I had, gnoshing on the occasional egg roll here and there, until the summer between my junior and senior years. I was sharing a duplex with two fellow students, Norm and Clint, and they both went home for the summer. I stayed in Athens and worked a truly craptastic job at a telemarketing place - which is why I’m more polite to telemarketers than most people are - and it was at that point that I found myself facing a dilemma:

I had enough money to keep paying rent and buying groceries, and I had enough money to pay tuition for Fall Quarter, but I did not have enough money to do both of those things.

I tried to conserve as much as humanly possible, and what that turned into was a six-week period during which I boughtno groceries, and instead lived off whatever I could find that Norm and Clint had left in the cabinets when they moved home. (I remember one day in particular when my food intake consisted of one can of sliced peaches. Those were some freaking delicious peaches.) Basically, for those six weeks, I did three things:

- worked at the telemarketing place for slightly less than peanuts, because we were on commission and I couldn’t sell a warm coat to an Eskimo

- learned to live with hunger pangs

- worried.

And oh, I got good at worrying. I’d lie on my bed and stare at the ceiling and just worry my heart out. To this day I’m sort of amazed that I didn’t give myself either a raging ulcer or some form of cancer.

The way I saw it, grocery boycotts aside, I had an extremely unpleasant yet unavoidable situation bearing down on me: I was going to have to drop out of college, move back in with my parents, and get a job at the local carpet mill. Taken individually, none of those consequences were all that bad. People took a quarter or two off from college all the time; moving back in with Mom and Dad would mean a familiar roof over my head and all the brilliant home cooking I could eat; and the local carpet mill paid relatively big bucks, especially when compared with Spencer Gifts or the telemarketing outfit. But I didn’t want to take that route, because in my mind that would mean I had failed, and I HATED the thought of just plain failing.

So I made cold calls to people who very pointedly did not want any magazine subscriptions, and I rationed my peanut butter crackers and canned apple sauce, and I worried.

The phone rang one day right around the middle of the summer, about two weeks before I had to pay tuition, at a point when I had just about perfected worrying into some sort of psychokinesis. I had fully intended to use my new worry-fueled and possibly hallucinatory mental super-power to bore holes in the ceiling, because I was too weak from hunger to get out of bed, but instead I answered the phone.

It was Dan Thorsland from Dark Horse, and his words might as well have been a magical incantation, they turned my world around so fast. “Hey Dan,” he said, “Do you think you could take over on this Colonial Marines mini-series and wrap it up in a couple of issues?”

It was as if the Heavens had opened for me.

FACEHUGGERS & OTHER CUTE CRITTERS: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 6

When senior year of college got started, not only did I have enough money to pay tuition and keep a roof over my head (thanks to Aliens: Colonial Marines), but I also traded up after-school jobs. I had spent junior year toiling away in the somewhat off-color world of Spencer Gifts, but the final year of my under-grad degree in English saw me working as an editor at Student Note Service - a place that, little did I suspect at the time, would figure prominently throughout my twenties.

The way Student Notes worked was that they’d put an ad in the school paper along the lines of, “Want to get paid to study? Call this number!” Students invariably came in, and they’d explain the drill: you go to class, take good notes, then come in and type those notes onto one of their computers. An editor - usually a grad student, but in my case, just a big nerd - would go through and polish the notes up. Then the business printed them up and sold them to other students in the class as “supplemental study guides,” with the understanding that they were not to be used in place of going to class, and that if there were any discrepancies between your notes and theirs, you were to use your own.

Did students use the notes in place of going to class? Of course they did. But if they bought notes that I had edited, they could at least count on them being factually accurate and grammatically flawless.

Working at Student Notes paid better than working at Spencer Gifts, but it was hardly what you’d call a gold mine, and I was still keenly interested in making an extra buck if I could. If that extra buck involved making up a story or two, I was all over it. So when Dan Thorsland called me up not long after school started and offered me another job, I said yes before he’d even explained what it was. If I had heard all the details first, considering what it turned out to be…I still would’ve said yes.

Here’s the thing I was quickly and thoroughly learning about being a fledgling freelance writer: when someone asks you, “Can you do _______?” the answer is always, “Why yes! Yes I can!”

THEM: “Can you come up with a story about a unicorn and a time-traveling toad?”

YOU: “You bet I can!”

THEM: “Can you fix the dialogue in this story so that it sounds appropriate to late 19th-century England?”

YOU: “No problem.”

THEM: “Can you create a character that will fit into an established superhero universe who is NOT a) a martial artist, b) an expert marksman, or c) an ace computer hacker?”

YOU: “Consider it done!”

(That last one actually happened, and led to my creator-owned DC series Bloodhound.)

And of course you may have NO IDEA at the time how to do what they’re asking you to do - but are you confident that you can figure it out? Why yes! Yes you are! (And if you’re not, you should do your best to get that way.) When you get hugely successful, and make a publisher enormous gobs of money, then you can afford to pick and choose what you want to do. But when you’re first starting out - even when you’ve been at it a while - every job you get is an opportunity to get better at what you do, make some money, and further establish your reputation. Maybe your philosophy differs from mine, but I don’t turn down paying work. I’m not sure I’d know how to.

In any case, what Dan Thorsland offered me that autumn day was a job writing little tiny miniature comic books that were going to be packaged with several new kinds of Aliens toys. If I recall correctly, I did the Rhino Alien, the Snake Alien, and the Giant Facehugger.

I also did one starring a new Colonial Marine who wore a special kind of armor that let him disguise himself as an alien and move among them unmolested. I think he was known as “A.T.A.X.” I don’t remember what that stood for.

These comics were only twelve pages long, and that wasn’t the only thing about them that had been lopped off short: the pay was a good bit less, and the target audience was considerably younger than what I’d aimed for on my otherAliens work. The toy company said they wanted the stories aimed at 8-year-olds, but in my humble and not at all biased opinion, what they really wanted was Aliens meetsTeleTubbies.

But it was paying work. Collectively those three mini-comics paid for another quarter’s tuition, plus I got to work with my favorite artist again: John Nadeau. He did brilliant work, as usual, though I suspect he was less than impressed with my stories on the mini-comics. John is one of the more low-key people I’ve ever met, so it was hard to tell; he usually makes the comedian Steven Wright look like Jim Carrey.

So we did the comics, and out they shipped with the toys, no doubt to be flapped about and ripped up and trod upon by very small children across the country.

By this point, John and I had actually met and hung out, at the Dragon*Con convention in downtown Atlanta, and decided we got along pretty well. Well enough, in fact, that when he started doing some work for Valiant Comics, he offered to introduce me to his editor, Jesse “Hurricane” Berdinka. That led to a series of events that would prompt me to ask, “What exactly is an ‘inventory story’?”

BULL%$&# AND OTHER OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 7A

I was going to make this column all about my time writing inventory stories for Valiant Comics, and I still will talk about that in a future entry, but then I remembered an experience I had before I got to Valiant. It’s an experience I wish I hadn’t had, but hey, part of the reason I’m doing this is to put my mistakes out there front and center, so that somebody coming up the same path I took might be able to avoid them.

This is the kind of story that involves real people, real properties, and details that could be tracked down and verified—IF I used real names. I’m not going to. As I have commented in earlier posts, I’m really not interested in being sued for libel, and besides, the important parts are the situations presented and the choices made. Those are the same no matter what I call these guys.

The year was 1993. I was soon to receive my Bachelor’s Degree in English from the University of Georgia (a degree that, in and of itself, has helped me get ZERO jobs as a writer), and I was weighing my options as to what I wanted to do after I had the diploma in hand.

I don’t remember why I called Bill, a comics artist I considered a friend, but I wound up on the phone with him one spring afternoon. My question of “How’s it going?” led him to tell me that he was trying to get a new project off the ground, but wasn’t satisfied with the writer he had chosen for it. Summoning up some confidence and bravado that I did not in any way truly feel, I said, “What? You need a writer, and you didn’t call me?”

Bill apparently liked my moxie, as it were, and invited me to come to his place and meet the team he’d put together for this thing. It was going to be an ongoing, monthly sci-fi book called GALAXY 799, and just from what Bill told me about it I was intrigued already, so I piled into my sun-faded Ford Escort and went over to Bill’s apartment.

And I met The Team: Bill on pencils, a guy my age named Stu doing inks, and a friend of Bill’s named Terry who was going to serve double duty as letterer and editor. (The outgoing writer was a guy named Morris, and I remember meeting him once, though I don’t recall the circumstances. He seemed nice enough.)

I read the one script Morris had finished, and I saw why Bill wasn’t happy with it. In my carefully considered opinion (as if I knew what I was talking about), the pacing was kind of clunky, and the dialogue was way too on-the-nose. I thought I could do better. Bill decided to let me prove it, and gave me the task of re-writing Issue #1.

Now, some of you may be thinking, “Why was this artist handing out jobs? That’s not how the industry works.” And it’s not - at least, not now. But the early 90’s was a bizarre time for comic books. A grand, overblown, sort of ridiculous, very bizarre time. I’m not going to get into the particulars and mechanics of it, but the early 90’s saw a boom in the business that defied description. Comics that only sold 100,000 copies a month were getting canceled. The best-selling titles moved millions of issues at a time. Some people in the industry made a HUUUGE amount of money.

I was not one of those people. By the time I had a chance at becoming one of those people, that enormous boom had gone bust, and the industry hasn’t recovered from it to this day.

At the time, though, that period of prosperity was still very much in effect, and one of the people who had made a gazillion dollars was a guy in Philadelphia named Kurt Norton. He had created his own unique comic book series, found an enthusiastic and loyal audience, and just raked in the dough hand over fist.

Norton had so much money, in fact, that he decided to whip up his own little corner of the industry, populated by creators that he hand-selected and - this is the important part - funded himself. Essentially, Norton said, “Hey, Guy Whose Work I Like. Go make a comic book. Pick your own team. I’ll send you the money to pay them, and we’ll split the profits.”

That was how Bill had gotten into the position he currently held: he was one of Kurt Norton’s chosen few.

Anyway. I had my assignment, I was eager to prove myself, and I went home and re-wrote Morris’s script for GALAXY 799 #1. I don’t remember exactly how long it took me, but I know that I was back at Bill’s apartment one week later for another team meeting. I had faxed the script over beforehand, and when I got there, Bill and Terry and Stu all told me how much they’d enjoyed it. “We’ve definitely made the right choice,” Bill said, and I became the official writer of GALAXY 799. It was the first time I had been attached to an ongoing series, rather than a one-shot or a limited-run project. I was over the freaking moon!

We did a lot of dreaming at that meeting. Kurt Norton had sent Bill a breakdown of what the profit split would be at each sales milestone: if we sold 30,000 copies, we’d get X number of dollars, if we sold 60,000 it would be X times 2, or something along those lines. As the number of copies sold got larger, our profit from it reached (to me) astronomical heights. And as writer, I was guaranteed a 20% share when the cash came rolling in.

You know how I knew I was guaranteed that? Because Bill told me. He looked me in the eye and he shook my hand and told me so. I was thrilled; a handshake was certainly good enough for me. I don’t think it even occurred to me to get a written contract. Happy as the proverbial clam, I went home, wrote GALAXY 799 #2, and faxed it over to Bill.

This is the point at which everything began spiraling into the toilet.

I heard not a peep out of Bill concerning my script for issue #2. He didn’t call. Nothing. So, when I showed up for the next team meeting, I was quite surprised when Bill pulled out my script and, addressing everyone, said, “Well, it’s obvious this isn’t very good. It’s basically just a re-hash of issue 1.” He went on to rip the story apart as if I weren’t even in the room.

Full disclosure: the script for issue #2 WASN’T very good. I was still so green as a writer I could’ve been mistaken for Kermit the Frog, and yes, there were things about the script that were probably pretty stinky. But for anyone out there interested in becoming an editor or, say, someone who manages a group of writers, believe me when I say that it is a REALLY BAD IDEA to ambush a writer in front of a group of people and rip his work apart. Particularly if he hasn’t had the chance to fix what might be wrong with it or, worse yet, doesn’t even know you had a problem with it.

I was humiliated and furious. I tried to defend the script, but Bill calmly told me—still in front of everyone—how wrong I was, and how my work wasn’t good enough, and that I had better fix it or I’d be out the door.

I was humiliated and furious, yes, but I also really wanted this job. Doing my best not to choke on it, I swallowed every bit of my pride and got to work improving the issue #2 script.

BULL%$&# AND OTHER OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 7B

For the next three weeks, though, Bill’s behavior got more and more erratic. Part of not having a contract was that there were no clearly delineated roles; I thought I was part of a team, whereas Bill apparently thought that, since he was the connection to Kurt Norton’s money, he was the project, and we were all just his minions, to do exactly as we were told with no questions asked.

Sometimes that works. Truly. There are visionaries who spearhead projects like that successfully, and if you don’t like it, you’d better get the hell out of their way. Sometimes that works—but this was not one of those times.

Bill started talking about taking the series in directions that just baffled me, and if I voiced any objections, he shut me down without listening to anything I had to say. He and Terry went off and had long talks about plot elements and story details, didn’t tell me anything about any of it, then acted as if I should already know what they had discussed, and were surprised when that stuff wasn’t in my latest draft.

Bill also began referring to the money that Terry and Stu and I were getting for our work as “blood money.” He acted as if we didn’t deserve it, and that he really didn’t want to give it to us, and that if he weren’t a man of his word, he definitely would not honor our agreement. He scowled as he handed us our checks and said, “Fine! Go on, take it.”

Things came to a head at one team meeting when Bill said that a wordless panel I had written “was okay, except you left out the dialogue.”

I said, “Huh? Oh—no, that’s a silent panel. Nobody says anything there.”

Bill looked at me as if I were cognitively challenged and said, “Okay, well, you need to put in a caption or something.”

I stuck to my guns. Foolishly. “No, Bill, it’s—see, the guy’s running across the roof toward the helicopter. He’s by himself. He’s got no radio. It’s just a silent panel. It’s perfect.”

Bill turned away from me dismissively, said, “No, it’s wrong. Put a caption or something there,” and as far as he was concerned, that was the end of the discussion.

Except that by that point I was angry, and didn’t understand anything about picking battles, and I said, “Look, Bill, I’m not just going to blindly do everything you say. You hired me to tell a story. I’m not a servant here.”

(I was out of line there. It’s not unusual—at all—to be summarily overridden in scripting decisions. Editors do it all the time, and only some of the time do they tell you they’re doing it. Frequently you find out you’ve been re-written when you get your copies of the book. HOWEVER, Bill’s reaction to my being out of line was to get way way way out of line.)

I don’t remember if Bill said anything in response to my little outburst or not, but that night after I got back home, he certainly did respond—through Terry, who called me up and let me know that, because I had a poor attitude, Bill was reducing my share of the profits from 20% to 7%.

I called Bill the next day and, in an uncharacteristic attempt to confront a problem, asked him why he was angry at me. Bill got extremely emotional and agitated and finally said, “You haven’t said ‘thank you’ a single time to me since I brought you on board! It’s like you’re not grateful at all!”

Now, at that point, I should have said, “Okay, thanks but no thanks. I’m out of here.” Bill had made it very clear that he was the Lord God Almighty as far as GALAXY 799 went, and that the project was going to sink or swim according to his whims, and at that point I had zero faith in his ability as a storyteller or as a leader.

But three things kept me in place:

- The lure of all those comics-related millions still dangled in front of me

- I had seen other contracts, and even 7% of the profits was a lot more than the 1.2% or 1% or 0.5% that other writers got

- I was, deep down inside, kind of a little drip with no self-esteem.

So I smoothed things over with Bill the best I could, and I wrote Issue #3, and I dutifully faxed it in. I was determined, this time, to get Bill’s feedback on it before the next team meeting, so I called him—and got his answering machine. That was unusual; Bill normally answered after the first or second ring. I tried again—still no pickup. I left a message asking him to call me back. He didn’t.

I tried all day the next day. I left another message. Nothing. It was as if Bill had disappeared off the face of the Earth.

The team meeting was set to take place Friday evening—and Thursday night, Terry called me. After a couple of hems and haws, Terry told me that Bill had instructed him to let me know that they wouldn’t be using my script for issue #3, and that I wouldn’t be getting paid for it. And that was the end of my involvement with GALAXY 799 and with Bill. I haven’t spoken to him since.

BULL%$&# AND OTHER OCCUPATIONAL HAZARDS: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 7C

It’s pretty unlikely that this sort of scenario would even come up today, because the comics industry is in no way prosperous enough to have piles of discretionary cash lying around, waiting to be used to fund crazy new projects. But, based on this experience, here are some guidelines I would strongly suggest following:

1) As a freelancer—not somebody trying to break in, willing to take risks so you can finally get that first thing published, but a working freelancer—the only way you should work without a contract is if you’re writing for a company that usually works that way, and has a solid reputation for paying its contractors. Otherwise, get a contract.

2) If someone asks you to do work for them otherwise—whether it’s a “scrappy startup company” or even a good friend of yours—GET EVERYTHING IN WRITING. I would say it’s even more important to get things in writing if it is a friend. Clearly delineate exactly what everyone’s role is, what each person is going to be doing, and how any money involved is going to be used down to the last penny. Not doing that is a good way for everyone involved to become ex-friends.

3) Once you know exactly what everyone’s role is, don’t be afraid to stick to that. I’m not saying be a jerk; there’s no need to get in anyone’s face. But if someone starts to go off the rails on a project, there’s nothing wrong with politely addressing the issue and trying to fix it. Going to IHOP with the inker and bitching about the penciler might be fun, but it doesn’t solve anything.

4) If you can see that, despite all best efforts, a project is going to go off the rails anyway, don’t be afraid to walk away from it. If it’s in that bad a shape, you might not be doing yourself any favors by having your name attached to it.

I understand that that last point is sometimes easier said than done, believe me. I’ve been involved in projects that had, shall we say, drawbacks, but I stuck around either because it was opening new connections for me, or I needed the money, or both. You have to look at these things on a case-by-case basis.

If you get hired to relaunch a major character at DC, for example, and what seems to be the entire Internet descends upon you with torches and pitchforks and tells you that you suck and you’re raping their childhood and you shouldn’t even be allowed to write checks, well, sometimes you stick with it as long as you can because the publicity you’re getting from it is pretty good, and the steady paycheck really helps out in supporting your family. (Not that I’d know anything about that. ::cough:: Firestorm ::cough:: )

But if some guy you’ve never met before comes up to you at a con and says, “Hey, I’m starting up my own comic company, and I’m looking for writers!” and you start working for him, but then he begins insisting that every story feature the word “scrotum,” and when you meet him to discuss the next issue he’s being tailed by a plainclothes cop, and then you realize he’s living out of his van and wants to give you stock in his company in lieu of pay, it’s probably okay if you decide not to hang in there for the long haul.

I’m just sayin’.

(NOTE: neither GALAXY 799, nor the actual book whose title shall remain undisclosed, ever went to press.)

MASTER’S DEGREES & PRETENTIOUS JACKASSES: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 8A

I’m not sure exactly when I started considering myself a “real” writer, but I’m crystal-clear on when I decided to leave the world of academia behind. In 1993, I was all set to graduate from the University of Georgia with a Bachelor’s of English. Being an indecisive bonehead in my very early 20’s, I had no idea what to do with my life—I knew I’d keep writing, but at the time I was a long way from supporting myself with freelance work—so I applied to the UGA Master’s Degree program. Why stop being a student? I knew what student life was like. I was accustomed to writing academic papers. And from what I had heard, the thesis in the Creative Writing program was, to no one’s surprise, something creative, like a novel. I could write a novel for my Master’s thesis! Sure, why not? Never mind that Master’s-thesis novels were notorious for coming back from the reviewing professors “dipped in blood,” the red ink on them was so abundant. (In 1993, everything at UGA was still very paper-based.

The way you registered for classes, right up through my last year there, was to pencil in the little bubbles on a freaking Scantron card, go into the basement of the administration building, and slide the cards through slots in the wall, on the other side of which were human beings who fed them into a card reader. The card reader in turn let the people know whether or not you got into the classes you wanted in time, and then another human being would stand in front of everyone in the waiting area and call out the names of which students had made it into which classes. The year after I left? THEN everything went to online registration. Of course.)

Anyway.

During my second-to-last quarter of classes in the English department (the last of two quarters subsidized by Aliens: Colonial Marines money), I went to the department secretary and asked her for everything I needed to apply to the Creative Writing Master’s program for the following fall. She gave me a number of pamphlets and guidelines and wished me luck. According to all the material, I had to compile my best creative work, along with (my memory gets a little hazy here) something like a letter stating why I wanted to be in the program.

So I put everything together - I even made a nifty-looking booklet of my short stories, with little tabs sticking out so the professors could easily flip to each one - and turned everything in, right before the deadline, which was my standard operating procedure. I also included a check for the fifty dollar application fee. Part of applying for the Master’s program was an interview with one of the professors. I’m not going to use his real name here, for the same reason that I haven’t used other people’s real names in the past: I don’t want to get sued. And by not using his real name, I’m free to tell you that this guy was the most pretentious jackass I had ever met. Our interview included a section that went like this:

JACKASS: So, have you had any publishing experience?

ME: Well, I’ve been getting comic books published, on and off, for the last two or three years.

JACKASS: [long, contempt-filled pause] I wouldn’t let anyone else in the program know about that if I were you.

I walked out of that interview thinking, “Wow, what a pretentious jackass!” But I figured he was just one guy, and didn’t represent the whole Creative Writing program, so I decided to ignore him and let it go.

Cut to about two weeks later, to a conversation I was having with another Creative Writing Master’s applicant. “So,” she asked me, “what was your critical paper on?” Slowly, but with a rising feeling of dread, I said, “What critical paper?” She held up a little red pamphlet that I had never seen before, and said, “The one this asks for. …Didn’t you get one of these from the department secretary?” I went into full-bore panic mode, but on the off-chance that the other applicant was mistaken, I tore ass down to the department secretary’s office, where I asked her if the application process required a critical paper along with all the creative stuff.

The secretary said, “Yes, of course it does,” and held up that same little red pamphlet my fellow student had shown me. “It says so right here, very clearly.”

All the blood in my head fell into my feet. “But you never gave me one of those!”

With a haughty and very final tone, she said, “Of course I did.”

I left the office in a funk. All I could envision was the approval committee looking at my incomplete application and saying things like, “Well, this Dan Jolley guy certainly doesn’t take the process seriously. He didn’t even turn in all the necessary material.” So I went home, thought it over, then went back the next day and withdrew my Master’s program application. Instead I applied to the Journalism undergraduate program. Maybe, I reasoned, this was for the best; instead of subjecting myself to punishing, ego-bashing scrutiny of my creative talents, I could get a degree in something that might be applicable in the real world. The secretary didn’t seem to care one way or the other what I did, but she did refund my check for fifty dollars, which was a huge amount of money to me at the time. So it was sort of like a bonus for withdrawing, if you looked at it sideways.

Feeling more or less okay with myself, I finished out Winter Quarter and got ready for Spring Quarter, set to face the final few classes separating me from my diploma. One of those classes turned out to be taught by none other than Pretentious Jackass.

I became even less impressed with this guy once he started “teaching.” He was like the ridiculous old professor in Dead Poets Society who wanted to chart the merit of poetry by using a graph with X and Y axes—except instead of a graph, Pretentious Jackass had a checklist written down in a little notebook, and he wouldn’t let us discuss anything about a specific piece until we’d satisfied his checklist, for every single story or poem, all quarter long. I didn’t learn much in Pretentious Jackass’s class.

At one point, he told us in very flatly-stated terms, “The only thing worth writing is literature.” (He pronounced it “LIT-tra-tchoor.”) He then went on to say, just as matter-of-factly, “And you CANNOT make a living writing LIT-tra-tchoor.” I sat there and stared at him and thought, “Wow, you…have never been published.”

But all of that is secondary, in my mind, anyway, to Pretentious Jackass’s further involvement in my attempt to get into the Creative Writing Master’s program. On the first day of class, while I was sitting there with eight or nine other students waiting to get the syllabus, Pretentious Jackass came in, stared around the room for a few seconds, and finally settled on me. “Are you Dan Jolley?”

A little flat-footed, I said, “Yes…?”

He said, “Welcome to the Creative Writing Master’s program. You’ve been accepted.”

MASTER’S DEGREES & PRETENTIOUS JACKASSES: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 8B

I sputtered for a second. “But…but I, uh…I withdrew my application…”

Without missing a beat or changing expression, he said, “Oh. Well then, never mind.” And he started class.

Anyway.

I finished Spring Quarter, got my diploma, worked the summer at Student Note Service (getting a promotion to Assistant Manager along the way), and when Fall Quarter started, I dutifully reported to the first of my classes in the mysterious halls of the Journalism School. Long story short on my Journalism career: it took me a quarter and a half to realize that I really, truly, honestly despised Journalism.

I was fed up with higher education as a whole, honestly, plus I already had my degree in English… …so I quit. No more academics for me. The closest I ever came to going back to school was seven years later, when I took a class on International Horror Films at the University of New Mexico, and that was just for kicks. But leaving college behind was okay, I thought, because I started working full-time at Student Note Service, and that paid well enough for a bonehead in his very early 20’s to rent a cheap apartment with a roommate and put gas in his cheap car and buy cheap food.

And because, by that point, John Nadeau had called me up and offered to introduce me to his editor at Valiant Comics. The future looked pretty darn bright. Bright enough for me, anyway.

But let me tell you something about being a freelance writer and getting a college degree (or degrees). I’ve mentioned this before, but just to be as clear as possible: those letters you can put after your name? NO ONE CARES ABOUT THEM. You know how many times, over the last twenty-one years, an editor has asked about my education? None. None times. It doesn’t come up. Editors care about whether or not you can write, period.

Now, don’t think I’m telling you not to go to college. You should absolutely go to college if you can, because you’ll have a wealth of experiences you can get no place else, and if you get good teachers and work hard, you’ll learn a lot. Writers are like sponges, and every bit of the knowledge and skills and wisdom you can soak up will make you better at what you do. College is great. But if you think you’ll get work just because you passed all your classes and got your diploma, well, that’s where you’re wrong, I’m afraid. I don’t know if any of the people I’m working for right now even know whether I went to college or not. What they do know, and what matters, is that I turn in quality work, on time, without being a pain in the ass.

That will get you work.

A VALIANT EFFORT: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 9A

Most of the events I talk about in this entry — the comic book-related ones, in any case — have taken on a very hazy quality, for reasons that I will explain later on. If anybody who worked with me during this time wants to correct the sequence or details of this stuff, by all means, please feel free.

The year was 1994. I had been getting paid actual money to make %$#& up and write it down for two and a half, maybe three years at that point, but I was still firmly in “scramble mode” as far as getting more work went.

Almost every freelancer out there knows exactly what I mean when I talk about “scramble mode.” It’s that gut-churning time when you either don’t have any more work coming in, or you can see a definite end to the work you’re doing now and realize you’d better line something else up ASAP. (The only freelancer I know of who has never had to scramble is Gail Simone, who was asked to write the “You’ll All Be Sorry” humor column that got her noticed, and was then asked to write for DC Comics. I only hate her a tiny little bit for that.)

This was in the wake of the God-awful GALAXY 799 debacle, and took place at least in part during my comically unsuccessful foray into Journalism school. John Nadeau, with whom I had worked a handful of times, had started doing some penciling for Valiant Comics, and offered to introduce me to his editor there, an enthusiastic fellow named Jesse Berdinka.

(Everyone at Valiant referred to Jesse with some regularity as “Hurricane,” and for months I figured that was either because he was full of destructive energy, or because he really liked the University of Miami. Turns out he had an affinity for a mixed drink known as the Hurricane. I felt only slightly let down.)

Jesse gave me the lay of the land around Valiant at the time. They had a list of core titles, including Bloodshot (the gun-toting, sword-wielding hardass you see up there at the top), Rai, Shadowman, Harbinger, X-O Manowar, Ninjak, The Second Life of Dr. Mirage, Secret Weapons, Turok: Dinosaur Hunter, Eternal Warrior, and Magnus, Robot Fighter. When I started writing for them, Valiant’s sales figures were a thing of beauty, and had made them major contenders, right alongside books like Batman and The X-Men.

There was another editor there, for whom I would soon do some writing as well, named Maurice Fontenot, and he and Jesse reported to senior editor Tony Bedard. All of my scripts had to get approved by either Jesse or Maurice, and then by Tony.

Aside from John, the only other artists I remember there were Bernard Chang and Sean Chen. I got to meet them and Jesse and Maurice in person when I went down to MegaCon in Orlando, and everyone was really cool and friendly. It was a great atmosphere, and I was thrilled to be a part of the company.

“But Dan,” some of the more astute comic book readers in the crowd might say at this point, “I don’t remember you writing any of the Valiant titles!” And those astute readers would be correct, because what I wrote for Valiant were inventory stories.

INVENTORY STORY (noun): A one- or two-issue story that stands alone and does not affect the continuity of a comic book series in any way. Used to fill in production gaps when the regular creative team on a series falls behind schedule.

Mainstream comic books are published on what is supposed to be a strict monthly schedule. In general, an artist can do about one page per day, so, allowing for him or her to have at least a little bit of a life, a standard 22-page comic book will take about a month to draw. That way you get a fresh new issue of your favorite title every four weeks.

Unless something goes wrong.

Most comics are produced on the razor’s edge of going off-schedule. They shouldn’t be; if everything were perfect, you’d have somewhere between six and twelve fully completed issues in the can before the first one ever comes out. But that doesn’t happen very often, and what does happen very often is that the penciler gets the flu, or the inker has to drop everything and go out of town, or the writer takes an extra two weeks to turn the script in.

(That’s still completely alien to me. I just cannot imagine holding up production like that because the script isn’t done. I’m told that puts me in the minority.)

Anyway, if/when something goes wrong and the editor doesn’t have a book to send to the printers, he can pull out an inventory story that was done a week or a month or a year earlier, and slot that right into place, no muss, no fuss.

So I boned up on my Valiant comics and started sending pitches in to Jesse Berdinka. I don’t remember which one got accepted first, but I do remember that I wrote inventory stories for Eternal Warrior, Turok: Dinosaur Hunter, Secret Weapons, and Bloodshot. In fact, as I recall, the one I did with John Nadeau was a two-parter, and featured a crossover between Bloodshot and Secret Weapons. I wish I could remember what that story was called.

It involved a distress signal from an orbiting research satellite, and for whatever reason, Bloodshot and the Secret Weapons crew (which consisted of three men and one woman wearing super-suits, sort of like Iron Man) hopped on board a Space Shuttle and rocketed up to see what was going on.

I’ve mentioned before in this blog how significant seeing the movie Pulp Fiction was for me as a writer. Pulp Fiction came out in 1994, I had seen it not long before I started writing these scripts for Valiant, and because of that my dialogue underwent a serious shift.

The two guys in the cockpit of the Space Shuttle in my story were Bloodshot and Tank, the biggest, toughest member of the Secret Weapons team. Before 1994, if I were going to write a scene in which some superhero types were on their way up to a space station to investigate Something Bad, the dialogue would have been really stilted, really on-the-nose, and supremely awful — something like this:

BLOODSHOT: There’s no telling what we might encounter up there. I hope you’re prepared for anything.

TANK: Of course I’m prepared for anything. This is the kind of danger the Secret Weapons face every day.

BLOODSHOT: Good. Everyone’s counting on us to figure out what’s gone wrong.

Ugh. Just…ugh. Those words would never be spoken by anyone, under any circumstances, ever.

A VALIANT EFFORT: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 9B

Because Pulp Fiction gave me a crash course in natural-sounding dialogue, though, I decided to open that scene up — same setup, Space Shuttle blasting off, zooming up into the Orbiting Unknown — with this exchange instead:

BLOODSHOT: Are you serious?

BLOODSHOT: There is no way Spinderella is hotter than Janet Jackson.

TANK: I know what I like, man.

Is that award-winning dialogue? No. But it’s a HELL of a lot better than what I would have written pre-Pulp Fiction, and at least sounds as if actual human beings might have said it. I don’t regard Quentin Tarantino as the same kind of cinematic demi-god that a lot of people do, but I do owe him a debt of gratitude for that movie.

So I did my inventory stories, and continued learning things about writing, and really thought I stood a good chance of maybe picking up a continuing series and getting regular work for the first time. Everyone seemed happy with the work I was doing, so why shouldn’t I join the Big Boys Club and really start getting my name out there?

Well, as it turned out, 1994 was also the year that Acclaim bought Valiant outright and re-booted the entire universe, rendering all of my inventory stories inapplicable. Not only that, but the new people in charge were also thoroughly uninterested in talking to me. So I was dumped right out of the whole Valiant experience and back into “scramble mode”…which slowly turned into “well, I’ve got a day job, so I don’t guess I have to scramble too hard”…which turned into a great big depression-filled writing slump that lasted a full two years.

Not the proudest time of my life.

Plus, the reason the whole Valiant thing is all a bit hazy now is that, not only did none of the scripts I wrote for them ever get published, but at this point I’ve changed computers and moved households often enough that I don’t even have any of those scripts anymore. All of that material has just evaporated.

Maybe I’ll try to track down Jesse or Maurice and see if they kept any of it.

MY FIRST REAL NOVEL: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been, Part 10

As I mentioned in my last post, what followed my brief foray into the world of Valiant Comics was a two-year-long stretch of absolutely nothing. The Valiant that I had written for no longer existed, none of the other editors I knew had any work to hand out, and as far as editors I didn’t know, none of them were in the least bit interested in talking to me.

(That didn’t stop me from cold-calling people, at least for a while, until I got discouraged. Sometimes cold-calling works. Other times it results in Bob Schreck telling you in no uncertain terms that no, you are not going to be given a chance to write Green Lantern.)

That two-year dry spell is the only time since the age of 13 that I ever considered not being a writer. Even then I wasn’t really serious about giving it up, but I was pretty down on myself, and my parents were not yet convinced that it wasn’t a huge waste of time; so during one phone conversation with my mother I remember saying, “Forget this comics stuff. I’ve got a job. I’m a businessman.”

As soon as those words came out of my mouth, though, I knew I was lying to myself. I just didn’t know what to do about it. I made a few efforts at connecting with artists, trying to get some indie projects going, but as any writer who’s ever tried to get an artist to work for free has no doubt discovered, that’s a lot easier said than done. Not that I blame artists for wanting to get paid; it’s their job. Of course they should get paid. But I was broke as hell and couldn’t pay them anything, so the comics I was attempting to put together were all still-born.

Eventually my depression worsened. I had begun thinking of myself as a comic book writer, and with no comic books to write, my sense of self-worth just got lower and lower. I wasn’t a lot of fun to live with during this period, as my house-mate at the time, Josh Krach, would no doubt attest. I was always angry, flew into rages at the drop of a hat, and probably seemed like a truly miserable person.

I never stopped thinking about writing, though, depressed and angry or not.

One of the comics I tried to get an artist on board for was an idea I had had in my freshman year of college, involving a character called “The Priest,” that came to me while watching a re-run of The Equalizer. That character eventually got overhauled and mutated and became Jürgen Steinholtz in the Top Cow mini-series Obergeist, but at the end of 1995 he was still The Priest, and I still wanted to do something with him.

I don’t remember exactly when it occurred to me that maybe I could write something that wasn’t a comic book script, but one day I came to that conclusion…and what made most sense to me at the time was that I should turn The Priest into a screenplay. After all, screenplays are written in script format, and wasn’t script format what I was most comfortable with? Of course, I didn’t really know anything about writing screenplays, so in preparation for my tentative foray into the medium, I decided to hit the bookstore and do some research. (The Internet was barely even a thing in 1995, and at that point I was still pretty hazy about what a “browser” was, so yeah, I hit the real, actual books.)

And that’s where Quentin Tarantino rears his head again.

The book I settled on at the local Barnes & Noble was an edition featuring two of his screenplays: Reservoir Dogs and True Romance. I brought the book home, ready to absorb all of his techniques and nuances…but what I read first was his introduction, in which he stated (and I’m paraphrasing), “Film is a highly collaborative medium. Whatever you write in your screenplay, it will be changed, and it will be out of your control. If you want to write something over which you retain control, write a damn novel.”

I sat there staring at those words for who knows how long.

Of course I wanted to retain control over my concept. It was my concept, wasn’t it? But I hadn’t written prose in years, and when I had, it was only very short short stories. Could I write an entire book? The thought of it was terrifying. Novelists seemed to me to be a variety of mythical creatures, almost, a breed of demi-gods. Did I have the nerve to try to be one of them?

But the more I thought about it, the more I liked the idea. No outside interference in the creative process. No other people to depend on. The whole thing would rest squarely on my shoulders. So, yeah, as it turned out, I did have the nerve. I had a Saturday off from work, so at about 11:30 that morning I sat down in a chair in my living room with an oversized sketch pad in my lap, and started making notes. The notes became an actual outline after an hour or so, and by 2:00 that afternoon I had started filling in a few details. I don’t know what sort of change had come over the expression on my face or the tone of my body language, but Josh got home at about 4:00, took one look at me sitting there scribbling notes, and said, “Oh—you’re back!”

He was right. The depression lifted. I got a lot less angry.

And I never again entertained any thought at all of not writing.